I have never participated in organized religion. I wasn't brought up in a religious household, there was little to no talk of spirituality in my upbringing. And yet I've had a strong sense of it for as long as I could remember. Of course I went through the rebellious anti-establishment phase, where god was as bad as government and nothing was important, and I keep a few tinges of that attitude in my personal philosophy still. I think religion as an establishment, especially as a powerhouse, has predominately negative consequences. But as far as my spiritual identity is concerned, I am open to many philosophies and am often inspired by religious doctrine and ritual.

Piscine Patel’s spiritual identity crisis in Life of Pi is something I can particularly relate to. When I was in elementary school, all of my friends were very active in the Christian church. I went to their houses and prayed before dinner. I woke up after a slumber party and went to church with them. I even spent a summer at vacation bible school. To my parents, this was just a side-effect of my social life. But one night at dinner when I asked them why we didn’t pray, and suggested we should, they did not take my new-found religious passion seriously. And rightly so, it was just part of an identity crisis resulting from my unconventional upbringing in a highly conventional neighborhood. But what if I had been serious? What if like Pi, "I just want(ed) to love god(p. 87)?” What if I had felt there was some spirituality, some sense of wholeness, th at I was lacking because of my family’s lack of religious faith? They wouldn’t have understood. But at that point, it wouldn’t have mattered. But because my ‘quest for God’ was just an effort to fit in, they made me realize that that kind of conformity is what’s dangerous about religion. By not taking me seriously, they made me realize that spirituality is not about praying before dinner, that it’s not about going to vacation bible school. It’s highly personal, and like for pi, it transcends the boundaries of establishment.

at I was lacking because of my family’s lack of religious faith? They wouldn’t have understood. But at that point, it wouldn’t have mattered. But because my ‘quest for God’ was just an effort to fit in, they made me realize that that kind of conformity is what’s dangerous about religion. By not taking me seriously, they made me realize that spirituality is not about praying before dinner, that it’s not about going to vacation bible school. It’s highly personal, and like for pi, it transcends the boundaries of establishment.

fun-times at vacation bible school

source: http://www.oklahomabrethrenassembly.org/W2vbs.gif

I started my true spiritual journey as an atheist. I did not believe in a singular god who had a continuous presence in our daily lives. But I still believed in a greater meaning – whether it be the harmony of nature or personal success, or simply the quest for joy in life. But as Pi says about atheists, “they

go as far as the legs of reason will take them – and then they leap (p. 35).” My leap is the one that I see all serious scientists –

especially physicists – having to take at some point in their careers. My leap is faith in the infinite, or more precisely, the infinitely small uniform composition of matter. Within that infinite rests a force – the force that causes all physical reality, the first force that determined the history of everything. To believe in this force is to have faith, my faith, in the idea that everything is connected, and everything follows a path of elegant uniformity.

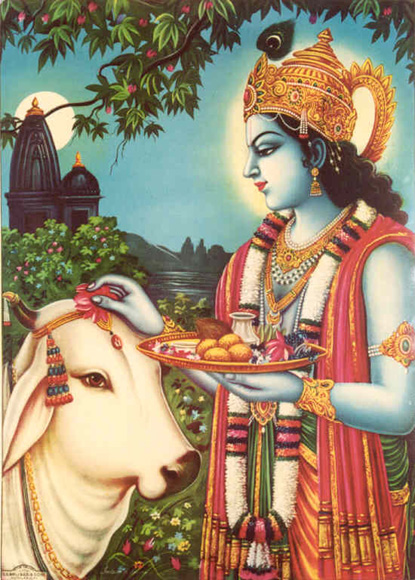

an elegant, uniform universe

source: http://www.fas.org/irp/imint/docs/rst/Sect20/heic0309.jpg

My faith may seem to be purely philosophical in nature, an abstract concept meant to create an elegant meaning of the universe, but I think, like all religion, it has greater humanitarian applications. Like Pi, “to me religion is about our dignity, not our depravity (p. 90),” and in a universe where all pheno

mena can be explained by activity occurring on infinitely smaller scales, our dignity is always maintained. All people – all matter – follow the same laws, despite seemingly different intentions.