Thursday, March 4, 2010

SIDDHARTHA DISCUSSION OUTLINE

Our meditation today: listening to music

By focusing our upper-mind on listening to repetitive, calming sounds, we can better focus our lower thoughts, or our subconscious thoughts, and perhaps reach a state of focused, calm, energy.

AND NOW TO CONTEMPLATE SIDDHARTHA’S JOURNEY TO INNER PEACE:

What is the significance of Siddhartha’s pilgrimage and how does it relate to your life?

His position afforded him luxuries which many people can’t have which undeniably altered his path

-Katherine

If Siddhartha had not acted on his decisions, if he had not lived with the Samanas or merchants, he never would have been able to make his own judgments on life

-Helen

As how Siddhartha learned an immense amount of wisdom from listening to the river, we can learn from keeping an open mind and listening to the ones we meet on our pilgrimage

-Jade

He had spent his entire life on a journey seeking spiritual enlightenment, just as I had spent my entire life on a journey to become an Olympic swimmer. I felt so much pressure to please the people around me, to not let them down, that I tortured myself to reach that goal

-Spin

This idea of unified change throughout life, of one person really transforming into many different people, is not a completely unfamiliar one

-Lauren

I do not think I could achieve enlightenment just following this simple path

-Emily

What did Siddhartha’s pilgrimage accomplish? Was it a necessary path to take?

I think that the human ability to transform ourselves, to mature, to become (hopefully) better, more caring people as we grow older, to gain wisdom through living life, though "it can't be expressed or taught in words" (Hesse, 132), is special.

-Lauren

We will be continuously seeking. Yet while obsessing over achieving a goal, we will not be open to the answers all around us

-Jade

Siddhartha spends a majority of the novel over thinking his life, tackling everything with a philosophical and spiritual approach. Eventually, he learns the wisdom of just letting things “be”

-Chris

Siddhartha and I both realized that this journey we were so desperately trying to make reach a “perfect” climax was not something that can be forced. It is something that - when you let go, relax, and just let it flow like a river - comes naturally.

-Spin

There is no “right!” We can search all we want for the true path, but we’ll “never stop searching.”

-Katherine

Is suffering necessary to reach a state of inner peace? What constitutes suffering?

Oftentimes we must go through hardships to find what our true beliefs are

-Jade

I am not entirely dissatisfied with the world—I see room for improvement, but I understand that I am a part of this world and I can work to improve it instead of setting myself apart.

-Emily

“I’ve had to experience despair […] in order to be able to experience divine grace,” (Hesse, 91) and it has definitely been worth it.

-Spin

Is suffering a byproduct of love? Is this why the ‘childlike’ people cannot escape from their suffering?

Siddhartha’s struggles with his son mirrors lovesickness in many ways–the devotion, envy of others’ happiness, loss of self

-Molly

How does unity lend itself to all encompassing love?

I continue to seek to see all things, all beings of the world, with love and appreciation

-Helen

Wednesday, March 3, 2010

EVERYTHING IS.

Today has been radiant. Today has been reaffirming, beautiful, unified, and complete. The sun is shining on my back, the grass is cool and soft, dandelions are perking up around me, bees going about their labor. I have been joyful all day. This is how the world should always be. Even in inclement weather, witnessing life around me should be the ultimate source of joy, and it often is.

is cool and soft, dandelions are perking up around me, bees going about their labor. I have been joyful all day. This is how the world should always be. Even in inclement weather, witnessing life around me should be the ultimate source of joy, and it often is.

Enjoying the beautiful day outside.

photo credit to author

Why did it take Siddhartha so long to find what he was seeking? This is the main question I have of his pilgrimage. I feel he knew his conclusion all along. But I suppose this is the lesson of misguidance. He knew where truth lie, but he was diverted from it by lessons and words, constructed dichotomies, and the pursuit of quantifiable meaning. Aren’t we all… I find myself retracing my own steps, through philosophies, sciences, teachers – all meaningful, none satisfactory. But these are the paths we are left to take. It is frustrating and circuitous sometimes to seek all within yourself, it is an easy task to give up on. We must find where to take our measurements, when to pin down the constant inner monologue that is the truth as it exists from moment to moment. But what we most often find is that those moments contradict each other. It is living in the contradiction, not trying to reconcile everything.

Because everything is. It’s a simple lesson that Siddhartha learns through a complicated life, and a lesson I often fall back on. I suppose it may seem trivial, naïve even, to be content with such an explanation. But it is so obvious when you sit and listen and observe that being is enough. Being as everything else is. This satisfaction with existence as it is – and whatever that implies – has many applications in our dealings with one another. The “awareness and conscious thought of the unity of all life (p.121)” brings us to realize that we are all of the same material and have the same potential for existence in one form or another, or in no form. By recognizing that potential, we recognize something worth loving and admiring in everything and everyone around us. As siddaharttha tells govinda, “one has to worship within themselves, in you, and in everyone else the buddha which is coming into being, that is poss ible (p.133).” In this case I take the Buddha to mean our potential for pure love and happiness, for a state of nirvana so-to-speak. By seeing this potential we are “able to look upon it and [ourselves] and upon all beings with love, admiration, and great respect (p.137).”

ible (p.133).” In this case I take the Buddha to mean our potential for pure love and happiness, for a state of nirvana so-to-speak. By seeing this potential we are “able to look upon it and [ourselves] and upon all beings with love, admiration, and great respect (p.137).”

We are all part of one earth, one universe.

source: http://greenerloudoun.files.wordpress.com/2008/01/nasa_earth.jpg

It is difficult to achieve this in a society that is based on competition, or in Siddhartha’s case, a society based on the differing values of individuals according to a caste system. So it is a cycle we must escape from, like samsara, but must still appreciate as a manifestation of the perfect universe we exist in. Although Siddhartha experienced the negative consequences of living in the sin of “the childlike people”, he still “saw people living for themselves, saw them achieve an infinite amount for themselves, saw them travel, wage war, suffer an infinite amount, and endure an infinite amount. He could love them for it, and he saw life and that which is alive - in each of their passions and actions (p.121).” So we must let go of our judgments and classifications, and allow everything to exist in its current form with the knowledge that it has the potential to occupy any form, including our own. I hope that despite our attempts to categorize the world, to explain the minutae of life, we can “learn to leave the world as it is, to love it, and to enjoy being a part of it (p.134).”

Monday, March 1, 2010

FALLING LEAVES

But how do we reach this state of being? Even Siddhartha, after going through the rigors of ascetism and the learning of a Brahmin, cannot hold onto the sublime state of moving independently through life. What hope do we have, constantly bombarded with materialism and fed the opinions of others? We are indeed “like a falling leaf that is blown and is t

urning around through the air, wavering and tumbling to the ground (p.69).”

urning around through the air, wavering and tumbling to the ground (p.69).”Siddhartha did not find nirvana.

source: http://www.wikiwak.com/image/Ascetic+Bodhisatta+Gotama+with

+the+Group+of+Five.jpg

Hesse’s book has given me a lot to contemplate thus far, and I am curious to see how this problem gets resolved. How does one hold onto a supreme sense of self, capable of overcoming any worldly trial, without becoming completely detached from the actual world of humanity? We must constantly sacrifice parts of ourselves to function within a society; I watch it happen everyday. We must then decide if that loss is outweighed by what we gain from human interaction – whether it is a physical relationship like that between Siddhartha and Kamala or a deep friendship like that between Siddhartha and Govinda. I think that the balance depends on surrounding yourself with the right people. Siddhartha maintained his love f

or Kamala because he saw in her a similar soul, but had to sacrifice that relationship because he was disillusioned by the other people he had to interact with.

or Kamala because he saw in her a similar soul, but had to sacrifice that relationship because he was disillusioned by the other people he had to interact with.We are all like falling leaves.

source: http://problemamuslim.files.wordpress.com/2009/05/falling_leaves.jpg

I can relate to Siddhartha in many ways. His constant yearning for an ultimate knowledge and his revelation that certain types of knowledge are not to be attained by learning mirrors my own. I have sought much by looking first inside myself rather than looking towards others, and like Siddhartha, “my trust in words that come from teachers is small (p.25),” not out of disrespect, but out of an understanding of the relativity of truth. I face many of the same contradictions in my daily life as Siddhartha, mainly in my attitudes towards other people and the importance of the self in attaining a nirvana-like state of existence. Sometimes I feel like Siddhartha felt when “he saw mankind going through life like a child or an animal that he both loved and despised at the same time (p.67).” I often feel disconnected from the culture I’m entrenched in, despite being a large participator in its daily manifestations. In the end, my goal is happiness, the cessation of suffering, and as Hesse’s book reaffirms, a weighing mind and constant moderation is a way to attain that goal.

Thursday, February 25, 2010

MORAL IMPERATIVES FOR ENVIRONMENTALISM

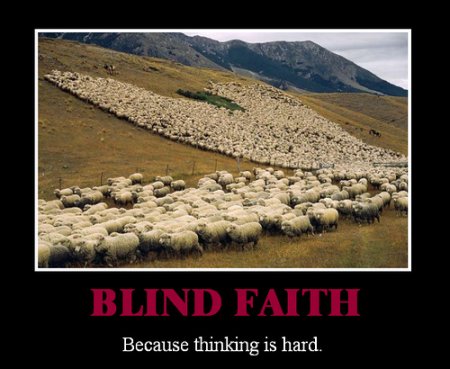

heir correlation support the validity of environmentalism, of religion, or of both? I think that this task of trying to find a moral imperative to be environmentally conscious overlooks the scientific fact of man’s place in nature. If we destroy our planet, we won’t be able to live on it, plain and simple. I don’t really understand why this logic isn’t enough to encourage people to think more sustainably towards the future, but since it obviously isn’t, we must create moral imperatives for them in the only thing they seem to believe blindly, religion.

heir correlation support the validity of environmentalism, of religion, or of both? I think that this task of trying to find a moral imperative to be environmentally conscious overlooks the scientific fact of man’s place in nature. If we destroy our planet, we won’t be able to live on it, plain and simple. I don’t really understand why this logic isn’t enough to encourage people to think more sustainably towards the future, but since it obviously isn’t, we must create moral imperatives for them in the only thing they seem to believe blindly, religion. Religious faith is sometimes the only source of moral imperative

source: http://petursey.files.wordpress.com/2009/10/blind-faith.jpg

We’ve already discussed Western religion’s role in this, and how its view of compassion can be selectively applied. In Jainism, however, who, or what, the moral code protects is strictly delineated. Following the path of Ahimsa, humans must not harm nor think of harming any living thing, plant or animal. This comes from “the development of a mental attitude in which hatred is replaced by love (236).” Love for all things and people within creation, stemming from a shared divinity of life. The implications for this in environmentalism are obvious. However, such a path is not enough to mitigate the affect man has on the environment. Would a Jain monk understand the long term implications of releasing carbon dioxide from burning fossil fuels? Or the interruption of natural land progression by suppressing the periodic burning of scrubland? What about the overpopulation of deer which results in the end of oak regeneration? In these instances, ahimsa is not enough, unless coupled with a deeper understanding of the implications of all our actions, not just those that result in the direct destruction of life.

Jainism does have a positive effect overall when put in the context of human relations. The idea that “one self dwells in all… by serving another, you serve your own self (237)” speaks to the unity of man as a species. From that perspectiv e, ecology arises once again as a central issue. If we are all each other’s protectors, if we all dwell in a singular self of existence, then we have a responsibility to maintain a suitable environment for that singular self to continue to exist. Thus we protect the environment for the future success of human life.

e, ecology arises once again as a central issue. If we are all each other’s protectors, if we all dwell in a singular self of existence, then we have a responsibility to maintain a suitable environment for that singular self to continue to exist. Thus we protect the environment for the future success of human life.

What are we leaving for future humans?

source:http://www.thedailygreen.com/cm/thedailygreen/images/beautiful-nature2-pp-www-lg.jpg

But what does this interpretation say of morality? That it is fueled by self-interest? I don’t think most Jain scholars would agree, from what I have read in the anthology and on the theory of ahimsa in general. In the essay on Jainism and ecology it argues that “we have a moral obligation toward nonhuman creation (145).” But where does that morality come from? Is it a spiritual creation, a respect for the divine natural world, or a humbled view of human accomplishment in the face of nature? This does not seem self-serving, but rather depreciative of humanity, and I think this is one of the main differences in Eastern and Western spiritual tradition. As the essay says, “the most urgent task of both science and religion is to assert the unity and sacredness of creation, and to reconsider the role of humans in it (245),” and I believe that Jainism fits that role. In western tradition, however, the sacredness of creation has been asserted, but man continues to dominate its trajectory.

It is a good question to ask what role man is to play in the “divine” theatre that is nature.  Will we be shepherds or slaughterers? Will we take what we need, or take what we want? We recognize the importance man has in interacting with nature, caring for it, using it to serve the species, as it states “agriculture is the noblest profession (241),” but where do we draw the line? What perspective do we take on the environment and our responsibility, our moral imperative, to protect it? When viewed from a spiritual perspective, we must consider where divinity lies, or to be less secular, where the beauty of creation is manifest. And this is the difference between eastern and western thought, for in the east divinity lies in all nature, but in the west it lies in man and in gods work through man. So if we could merge these two perspectives, superimpose them on one another, we’d be left with a question similar to Professor Bump’s: “who would not be upset if a saint was lopped, maimed, and killed? (222)” The only difference lies in who your saints are, but regardless, it is agreed that the divine should never be destroyed.

Will we be shepherds or slaughterers? Will we take what we need, or take what we want? We recognize the importance man has in interacting with nature, caring for it, using it to serve the species, as it states “agriculture is the noblest profession (241),” but where do we draw the line? What perspective do we take on the environment and our responsibility, our moral imperative, to protect it? When viewed from a spiritual perspective, we must consider where divinity lies, or to be less secular, where the beauty of creation is manifest. And this is the difference between eastern and western thought, for in the east divinity lies in all nature, but in the west it lies in man and in gods work through man. So if we could merge these two perspectives, superimpose them on one another, we’d be left with a question similar to Professor Bump’s: “who would not be upset if a saint was lopped, maimed, and killed? (222)” The only difference lies in who your saints are, but regardless, it is agreed that the divine should never be destroyed.

Nature is divine.

source: http://static.flickr.com/63/171449609_ca3f8640df.jpg

Wednesday, February 17, 2010

RELIGION AND THE ENVIRONMENT

At first glance, there might not seem to be much of a correlation between religion and environmentalism. However, as we saw in our own discussion of spirituality, many of us have a profound connection with our natural world, in the presence of which we often feel closest to the divine. But how is that feeling reflected in religious doctrine itself? And how can this correlation be used as a tool to foster environmental awareness?

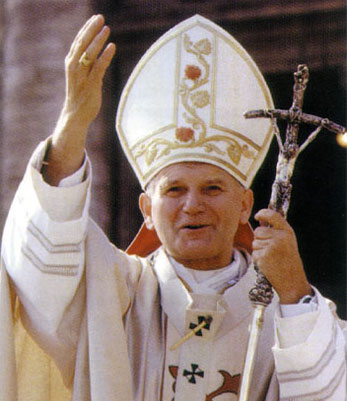

Western religions don’t have the best reputation for being environmentally conscious. Recently there have been adjustments, such as the Pope making pollution and environmental degradation an “official” sin, but overall, and judging by the bulk of their doctrines and practices, there is little room in their moral code for the protection of any life, or any environment, that isn’t human. As the essay on ecology and world religions stated, “religions have traditionally been concerned with the path of personal salvation, which frequently emphasized otherworldly goals and and rejected this world as corrupting (anthology, 28).” In most western religious tradition the moral code is focused on human interaction, and hu

mans are the only ones created in the image of god, and thus at the top of the hierarchy of life. And so the only way to relate western religion to environmental responsibility is through its human components. If we destroy our world now, where will our children and the children of our brother’s live tomorrow? A hint of this reasoning can be found in the Qur’an, as quoted in the anthology, “live in this world as if you are going to live forever: prepare for the next world as if you are going to die tomorrow (30).” But still, the concept of an afterlife makes it much easier for people to overlook the degradation of this life. As does God’s command in Genesis: "be fruitful, multiply. Fill the earth and conquer it (115).”

The Pope made pollution a sin,

but does that really reflect

catholic doctrine?

source: http://www.polishamericancenter.org/Pictures/pope-new2.jpg

The whole relationship, or rather disconnect, between god, man, and the environment creates many hurdles to using religion as a motivator in increasing environmental awareness. From the very start, man is separate from nature. However, in eastern tradition these separations stop. Man enters the world machine and is part of the cyclical whole of the environment and the cosmos. In this way eastern tradition is more conducive to celebrating a symbiosis with nature, and conservancy becomes the natural course of man.

The might of nature.

source: http://www.treehugger.com/forest-nature-scene.jpg

Despite differences in the two philosophies, it can’t be denied that religion is a powerful tool to promote certain actions of the part of the individual. By tapping into one’s spiritual beliefs, you tap into their sense of purpose, of duty, and of legacy. One thing that flows through all beliefs and all people, however, is the awe and power of nature as we experience it on earth. As Virgil says “see how it totters- the world's orbed might, earth, and wide ocean, and the vault profound, all, see, enraptured of the coming time! ah! might such length of days to me be given (124).” Even in the face of all our ascribed divinity and doctrine, nature still dominates our current space, and we cannot avoid the fact that the world around us will outlive us, whether we work towards saving it or not. Our bodies will die, and go back into the larger system of the earth, regardless of the destination of our souls.

Monday, February 8, 2010

THE END POINT OF A CIRCLE

plete separation from past identity, it is the end that is not death of body but a reemergence from the death of soul, or rather, the splitting of a soul.

plete separation from past identity, it is the end that is not death of body but a reemergence from the death of soul, or rather, the splitting of a soul.Could Richard Parker be an alternate

reality for Pi's sense of self?

source: http://thebeliever07.files.wordpress.com/2008/07/parker460.jpg

Pi’s end comes from an early realization that, “when your own life is threatened, your sense of empathy is blunted by a terrible, selfish hunger for survival (p. 151).” In his story he first loses an empathy that was once so easily engrained – vegetarianism – and later an empathy with far more profound consequences. Richard Parker lurks through this new reality, an example of unrestrained determinism, and a symbol of fear for Pi. But what does the tiger on the boat threaten? We do not know if it is threatening Pi’s survival of body, or whether it threatens to overtake his moral soul. Perhaps the threats go hand in hand, and so once again, in the end, the truth may remain relative.

And what of Pi’s loss? He maintains his body. He maintains a will. A wit. A God. Even a scrap of sociability. But he does lose something profound on the boat, he loses his mother. And what is more of an ultimate end than that? Pi says, “to lose your mother, well, that is like losing the sun above you (p. 160).” This is the final straw to sever pi from his place, to leave him disoriented in reality, and to start anew with another narrative, not of loss but of sacrifice. For a maternal chimpanzee is not a mother, a wounded zebra not a young sailor. And so the loss is not the same. It is not so much a loss at that point as it is a trade off, one life for another. Even to a zookeeper’s son, or especially to him, the circle of life is a firm reality, that is until man, until Pi, turns into the end point of the circle – and thus must work against it.

Pi suffers. Pi is lost. Pi is displaced, disoriented, removed. Yet Pi lives, and what is the most striking thing left in his life? It his ability to tell a story. To create a story where God exists, from a situation in which God, to most of us, would seem so far away. The most striking thing left to Pi at the ultimate end of his suffering is this realization – truth is rel

ative. Truth is relative to the end one wishes to achieve. Pi’s end is the same no matter the narrative, and he asks of his interrogators, “which is the better story, the story with animals or the story without animals? (p. 398)” Which is the better story, the better truth? In the case of ultimate suffering, it does not matter the means to the end. A soul is left ripped open, split, allowed to create whatever meaning it so chooses. And the meaning it chooses is the meaning that keeps some semblance of human wholeness, of order, of will. And yet it is the realization that these semblances are but that, mirages on an open sea, that affirms in the end the triviality of distinction. All that is left of life is to live, so it went with Pi, “and so it goes with God. (p. 399)”

ative. Truth is relative to the end one wishes to achieve. Pi’s end is the same no matter the narrative, and he asks of his interrogators, “which is the better story, the story with animals or the story without animals? (p. 398)” Which is the better story, the better truth? In the case of ultimate suffering, it does not matter the means to the end. A soul is left ripped open, split, allowed to create whatever meaning it so chooses. And the meaning it chooses is the meaning that keeps some semblance of human wholeness, of order, of will. And yet it is the realization that these semblances are but that, mirages on an open sea, that affirms in the end the triviality of distinction. All that is left of life is to live, so it went with Pi, “and so it goes with God. (p. 399)”be sought nor found.

source: http://www.therawdivas.com/HHH/images/truth-nextexit.jpg

Monday, February 1, 2010

PAST AND FUTURE ETHICS: With Heart Agape

A woman is walking down the street. Her universe is solid. Her thoughts busy but controlled. Her morning starts with tea and periodicals, every day. Behind her trail the rigid structures of her past decision making, a tessellation formed carefully and completely. Her path is clear in both directions, backwards and forwards.

A woman is walking down the street. Her universe is solid. Her thoughts busy but controlled. Her morning starts with tea and periodicals, every day. Behind her trail the rigid structures of her past decision making, a tessellation formed carefully and completely. Her path is clear in both directions, backwards and forwards.

'a tessellation formed carefully and completely'

source:http://mathworld.wolfram.com/images/eps-gif/DemiregularTessellations_600.gif

She’s an unshakeable woman, and not for lack of being shaken. She sees hardship daily at work. She sees it, enters it into the formula, and calculates the appropriate response. The heat has been shut off in nearly half the units on Avenue B. Bonham Elementary just cut 6 teachers. There are no proposed budget raises for the education sector – or any sector. Crime rates have risen. She has eighty-seven unread e-mails, all urgent, all the same. And at her desk, tea getting cold, periodical set aside, she makes decisions that chip away, slowly and deliberately, at the inefficient cycle that is American Poverty.

Here she sits - successful, moderately affluent, rigorously intellectual. She sees justice in everything, by constant judgment and classification. Her views shift with the circumstances, reason intact. She follows the path of constant resistance; a skeptic. She finds joy in making things orderly, connected, part of a greater whole. But to create unity, she is consistently destroying the individual. She recognizes differences, she recognizes even her own uniqueness, but she continues to lump things – and people - together. Differences are but runs in the perfect cloth of her universe - a tapestry that explains everything, growing at the edges with beautiful and ever intensifying patterns. Complexity grows, disorder fades. The heat gets turned on in unit twenty-seven.

Out for her second biodegradable cup of chai. Metallic ringing tells her that her father is calling. She considers her schedule – does she have time for awkward banter? Irritating questions? Too much time, it turns out.

“Hi Dad.”

“Hello.” A sob, broken. “She’s dead.”

It’s not the call she expected, least of all from him. And in one moment her formula has broken down. She has contemplated the event of her mother’s death before; that she is reconciled with. But her father was not accounted for. One would not call their relationship loving, at least not on her end. Resentful, yes, impatient perhaps, but she never allowed him her sympathy before, and considering it now made her extremely uneasy. How would she deal with this man, this sobbing man, for whom she fostered little respect and less affection? He would need constant attention, the same attention her mother had wasted so much time on. He was a very needy man, incompetent in the most basic of household duties, easy to fluster, easier to depress. She didn’t have time for this. She didn’t have the emotional capacity.

That dull feeling starts welling up in her chest. A precursor to sadness perhaps , the unmitigated sorrow she never gets to feel. And why not? Why now, when she has an excuse to break down, to reach out, empathize in a common situation with a fellow human being (family no less), does she feel nothing?

, the unmitigated sorrow she never gets to feel. And why not? Why now, when she has an excuse to break down, to reach out, empathize in a common situation with a fellow human being (family no less), does she feel nothing?

What causes emotional paralysis?

source:http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/20/Gray784.png

Worse than nothing, she feels the barrier, pressed so hard against that wall she could suffocate. All she has to do is show something, some scrap of love or compassion, pathos – but she can’t. And she traces back to the why, because that’s all she knows how to do.

I was fifteen and I could feel everything. The ills of the world were my passions – everything in my future set aside to solve them one by one. Dred-locked, revolutionary, I felt that the trials of those less fortunate were my trials to bear, oppression mine to defeat. Apathy was the ultimate enemy, ambivalence disgusted me. My motto – never be content.

And then I met him. His passion rivaled even mine (though I definitely had the better dreds). Where I came from a loving, stimulating environment, his had been broken. And so his passion, though just as strong, was somewhat fractured - energy with nowhere to go. His ills were now more important than the world’s. His sadness – unbearable. And so with the selfless love we all contain – agape – I poured everything I had into him. And for awhile I was approaching that contentment I so loathed.

Young romance may seem frivolous to some, but for us it was anything but. We were entrenched. For once we each had someone else to take us seriously – our optimism, our compassion, our grandiose schemes – finally we were sharing them. It was a tumultuous love between tumultuous people – one of those huge life relationships, compacted into mere years. And despite many of my more skeptical, cynical moments, I will never discount what we had because of its scale or age. And that is the hardest to bear.

We talk about a selfless love, spiritual, all-encompassing, divine love – but how many of us experience that? Perhaps we sense some abstract form of it through our religion or our connection with the environment, but to create that love between people is a rare and amazing experience. Once you’ve loved like that, you can never forget human potential for compassion. You can’t forget your own potential, even if it never rears its head again. And so I can’t forget this relationship. I can’t deny that it left me how I am. I can’t deny the potential it showed me.

But maybe I do. To lose a love like that – or rather to give it up – is debilitating. To give everything you have to someone – to be truly selfless in loving someone – well, it can cause you to give up too much for too little. I saw a man suffering. I reached out with all available compassion, all possible love, demanding so little – but perhaps expecting too much. I expected to alleviate suffering. To help him help himself and the others suffering in his life. But sometimes another’s suffering is not in our hands. Sometimes love is not enough.

So I gave up on love, I gave up on his suffering, as he had given up long ago. But it was too late; I’d spent my reserves. The passion I once had was diluted. My old optimism seemed naïve. Love was too painful a concept to appreciate. But ethics – my ethics remained.

At the end of it all, I would still not accept suffering as a fact of life. That would be indulging in my own weakness – a weakness I had learned from him. But the path to alleviate suffering was no longer abrupt, loving-kindness – it was never to be rushed along again. It was cold, calculating, relentlessly driven. It required a steady mind andpatient labor. Most of all, it required constant risk management.

So a life emerged: numb of compassion, withholding of love. But driven to compensate for the one failure that meant the most.

What is life now, in this numbness?

A woman is walking down the street. It’s cold outside, but she feels the residual warmth of the space heater she just dropped off at unit twenty-seven, Avenue B. The home of a student, met working the afterschool program at Bonham Elementary. A new baby brother, a single mother, no heat. But the warmth is there now, and she can still feel it. She passes the café, hands three dollars to the man huddled outside. The city’s budget may be frozen, but hers remains flexible – she chooses which commodities to cut and trade. Her phone rings. Her father – a kind man.

“Hi Dad.”

“Sweetheart, your mom…” A sob, broken.

A sob, echoed.

“I’ll be there. I love you.”

Once she thought she was numb to this kind of pain, this kind of love. Once she thought, it is no one’s right to suffer.

But those thoughts were fleeting. And she entered life again, with heart agape.

Life is nothing in numbness. So I go forward in my actions, I do not run out of fuel, I do not run out of love. There are many ways to apply ethics in our lives. Some ways help reach people most efficiently. Other ways help us reach them directly. When we combine both, keeping in mind all our past and possible future experiences, we can change lives – across the world and across our dinner tables. I plan to apply my knowledge and appreciation of justice, democracy, and social responsibility to a career that alleviates the suffering of a community – a society – at large. But I will never forget the love and compassion that flows through me, though I may try to guard myself against it. I know it is there, and I know it can make a difference in cases where reason alone, where the most complex of calculations, cannot control an outcome. And I will love as if love is limitless.

source:http://i260.photobucket.com/albums/ii31/sandralovescj/LOVE.jpg